The Appropriate Use of You-Know-What, You-Know-Where and You-Know-How

Perhaps I’m a little odd, but I have a thing about hygiene in Historical Romance. Whenever the captain of a buccaneering vessel sweeps his love interest into his arms and carries her into his cabin, I tend to wonder when he (or she) last washed. I know, I know; we are supposed to presume that our protagonist and love interest have taken care of the essentials, but the question of love’s bare necessities remains for me.

Perhaps my obsession comes as a result of the years I spent studying history, and the need to understand it at its contextual level. As a student, I was expected to research everything and assume nothing before attempting to offer my opinion. As there were no Regency rakes hiding in 19th century census transcripts, and little mention of heaving bosoms among the Old Bailey records, the hard graft of understanding the ordinary person took precedence. Then again, my sanitary preoccupation might be the result of my addiction to Time Team, and Phil Harding’s love of the ‘good tomato growing soil’ at the base of a castle’s long drop toilet system. Regardless, historical hygiene has always fascinated me.

Paula Lofting, author of Sons of the Wolf, is a childhood friend of mine, and our shared passion for our writing and our children has seen us through most of our lives together. When Paula’s debut novel began to take shape, and her ongoing involvement with Regia Anglorum fascinated me, I recall wanting to know all about pre 1066 England. So excited was I, that my first question was, ‘So, what did the Anglo Saxons use for toilet paper?’ It’s true; the University of Oxford conferred upon me a piece of paper assuring the world of my historical abilities, and I ignored the status of Anglo Saxon women, their societal structure, architecture, medical knowledge and so much more, to ask about the act of wiping one’s nether regions!

All buccaneers, rakes, heaving bosoms and moss wiped bottoms aside, I have to wonder if this is a subject considered by other Historical Romance readers. Are the undergarments, unmentionables and undesirables better left unsaid in Historical Romance? Personally, I believe that the more of life’s ‘little things’ there are in historical fiction, the more it can lend credibility to a good story. I’m not suggesting that a hero or heroine should be portrayed as an OCD sufferer in a ritual cleansing frenzy, and nor do I believe that a manifest of undergarments should be provided each time anybody disrobes. No; what I would prefer to see is the occasional, tasteful reference to how they kept themselves clean, and to ensure that it is appropriate to the era in which they lived.

This requires a fair amount of research, but it can pay dividends in terms of believability. The practise of soap making, for instance, is an ancient one, and lye soap has been used by everybody with access to animal fat, ash and a fire since time immemorial; possibly since before the Anglo Saxons were gathering moss for the purpose of wiping themselves! Lye soap however, was only fashioned into solid cakes when mixed with salt, and was definitely not to be applied to the face in that form; not unless the heroine was intent on ageing before a reader’s eyes. Soft lye soap was used for bathing, and was generally scooped from a pot with the fingers.

Toothbrushes too, have been around in one form or another for centuries, and toothpaste as we know it today since at least the 19th century. Before then, salt or charcoal were the most effective dental cleansers. There were no antiperspirants in days of yore, but deodorants in the form of powders and perfumes were in common use by the middling and upper classes since the Middle Ages at the very least. As to underwear, the simple act of having one’s bloomers (the precursors to pantaloons) removed in the late 18th and early to mid 19th centuries, required the removal of two separate legs, each joined by a tied fronts piece. This is the context about which I write when discussing historical accuracy and the ‘little things’.

Often in fiction, the most unmentionable of all subjects is a woman’s menstrual cycle; something requiring a well crafted and sensitive approach by an author. It is difficult to ignore the subject if a fornicating couple is trapped by marauding abductors for anything in excess of three weeks, as the inevitable will happen; from puberty to menopause, you can generally set your clock by it. Pregnancy too, is the result of sexual activity at a certain time in a woman’s cycle, and the credibility of a story can often hinge upon such trivialities as the moon and the calendar. Historical Romance authors should ignore these realities at their own peril; but how can they be addressed without risking it being overdone to the point of distraction? I believe that it’s all about balance, and I offer the following advice to those struggling with subjects from moss to menses, and everything in between.

Heroines can simply catch a glimpse of a little soap at the base of an earlobe, thus assuring the reader that her love interest is ship-shape in the cleanliness stakes. Alternatively, the hair at the nape of his neck might be damp from his ablutions, or his own musk might mingle with the aroma of lye soap as she falls into his embrace. When crafted as a passing mention, these details don’t detract from the scene itself, but they serve to give characters substance. The requirement for a certain level of cleanliness is something we share with our forebears, and thus it can transcend the ages and allow readers to relate; something all authors continually strive to achieve.

The inevitable ‘monthlies’ (a term used in antiquity, and still common in the 1950’s) are bound to crop up in a book spanning a time frame in excess of three weeks. It doesn’t have to be spelled out in gruesome detail, but the passing mention of a heroine’s cramps slowing her morning routine can convey to a reader that she is just as human as the rest of us. Childbirth too, can be an interesting subject, but many authors struggle between providing too much or too little information. If it is essential to the plot, a well written delivery (in history, the woman was delivered of the child; the child was not delivered) can add a wonderful dimension to a story. Again, this must be done in the context of the times, and in keeping with the heroine’s knowledge of childbirth. Words such as uterus, contraction, umbilical cord and birth canal have only been in general circulation in modern times, whereas pain, cramp, urge, sting and push are timeless.

Long underwear on men is another area of fascination for me. Although the nightshirt, nightcap and long undies of antiquity predominate in modern depictions of life in Tudor England, 19th century Midwestern saloons and colonial plantations, the truth of the matter is that not all men wore long underwear. To begin with, the impoverished Dorsetshire agricultural labourer had little chance of affording such a luxury, and I can assure you that no early Australian settler in his right mind would wear long woollen undies and trousers when the mercury hovered around the 110 mark for weeks on end. The latter labouring fellow would either cut out the legs from the offending undergarment, or opt to ‘free-ball’, in order to survive the rigours of his environment.

I suspect also, that stays, corsets, crinolines and bustles for colonial working class women were reserved for the advent of company, or for venturing outside of the homestead for church, as any restriction to working efficiently would necessitate its removal. Books and electronic sources detail what people wore in a certain era, and such resources contain wonderful descriptions and drawings of clothing and accessories, equipping the historical fiction author with everything they need to put a heroine’s ensemble together. The author must however, be wary of out-thinking daily life, and should acknowledge that life’s practicalities also come into the picture; after all, the flip-flop is not a modern invention, and was worn by the Japanese for centuries. As to the aforementioned night attire, it’s all very well to rug up for a night in a Hebridean crofter’s hut, but sweltering nights in the colonial tropics are best survived by wearing as little as possible under netting, thus allowing perspiration to help cool the skin.

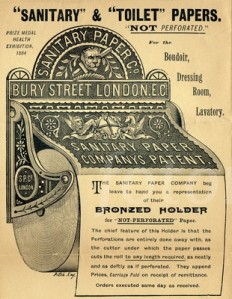

Finally, let us not forget the most basic function of all; toileting oneself. No romance reader, historical or otherwise, wants to be faced with the prospect of Lord Dunraven grabbing a copy of The Times and heading for his era’s version of the thunderbox; God forbid! The thought is as abhorrent as any mention of poorly functioning bowels, and any author in breach of this unwritten law should find a sturdy cane and administer themselves a damned sound thrashing. If however, mention of ‘the pot’ is appropriate to a scene, it should be tasteful, fleeting and non descriptive, and used only as a means of adding believability.

I admit that I like Historical Romances with the right doses of ablutionary reality in them, but only as a means of giving characters and situations believability and depth. I need to rest assured that a kiss allows a heroine to be the recipient of a man’s passion, and not the remnants of the pease pudding and faggots he ate for dinner. Most importantly, I strive to provide my own readers with the correct doses of subliminal reassurance that teeth are clean, nether regions are fresh and underwear is laundered, regardless of marauding abductors and the calendar.

It’s fairly late as I finish this Blog, and I’m well overdue for a you-know-what, you-know-how and you-know-where (hot cup of tea, white and sweet, in bed). I shall bid you all good night, climb into my 21st century night attire, and start thinking about my next Blog.